In the current political environment, everyone (from policymakers down to individual citizens) dismisses views that don’t align with their own by characterizing them as irrational or nonsensical. As I talked to a wide variety of folks in preparation for this post on security, I encountered that firsthand.

I was also struck by the false dichotomy created by the linguistic divide. Which is a $2 way of saying that 90% of the people I spoke to all hold the same beliefs but responded to questions differently based on whether I approached them using words more commonly used in their tribe or words used by the other tribe.

Politicians play into that because it assures them a base of voters. This is fine if you’re running for dog catcher but irresponsible when the position you’re running for has serious strategic responsibility and requires hard decisions.

It’s also dangerous because once a policymaker plays into that divide, they will never be able to gain consensus on important topics like security. They can’t gain consensus because once they leverage the partisan divide instead of proposing solutions, they immediately lose the support of ½ of the electorate. -Who they then label as irrational and deluded.-

If you think I’m referring to the other guy… (no matter which guy you favor) then you might be part of the problem too… ;-)

The result of policymakers leveraging tribalism to their benefit is made clear in the stunning results of a recent survey. The survey finds that “nearly two-thirds of Americans do not trust the federal government, a share that has increased over the last two years and marked a period of near record-low confidence in the country’s political institutions." 1

It’s probably ironic (and funny to someone) that the only thing that a large majority of Americans can agree on is that our policymakers are not trustworthy.

Even if we set aside the dysfunction of the two political parties and the spectacle of policymakers attacking the very institutions they are leading, we can see that the erosion of citizen faith in government has gone unanswered for too long.

-It certainly makes discussing wicked problems almost impossible without first reviewing the Marquess of Queensbury's rules.-

Our last post in this series (National Defense or Neighborhood Watch) began a continuing discussion about the massive gap between citizen and policymaker views on the meaning of “security.” As we return to that conversation, we recommend an essay written by General Maxwell Taylor in 1974.

Surrounded by protest and civil unrest (linked to the war in Vietnam, Civil Rights, and an energy crisis) all backlit by the Cold War struggle with the Soviets, General Taylor wrote an essay in Foreign Affairs entitled “The Legitimate Claims of National Security. "2 In that essay, General Taylor spoke about the danger of the divide between citizen and policymaker views on security.

General Taylor’s essay illustrates how citizens’ views on security have continued to diverge from policymakers’ views over time. This is not a new phenomenon, and it’s getting worse. Unity of effort and trust may sound cliche, but if “two-thirds” of Americans don’t trust the government, how long will our Union last when we’re forced to make tough choices?

General Maxwell Taylor is a bit of a controversial figure in military circles. In recent years, folks like H.R. McMaster have used a fine-toothed comb to look through General Taylor’s influence and decision-making in the run-up and during the war in Vietnam. I’m not debating the McMaster viewpoint in this post (and, God willing, McMaster’s legacy won’t be subjected to the same scrutiny he placed on Taylor’s)3 But, the debates about security that occurred during General Taylor’s lifetime make some of his insights invaluable to us in the here and now.

“National security… has come to signify in many minds unreasonable military demands, excessive defense budgets, and collusive dealings with the military-industrial complex.” Maxwell Taylor

In 1974, General Taylor worried that the American public was losing faith in its government, especially the defense enterprise. He warned that continuing the policies in place without having a more holistic discussion with the public about their views on security “threaten[ed] to price national security out of range of taxpayer willingness to pay.”

General Taylor wasn’t talking about “whether” we should defend America. He was simply worried that taxpayers would not be willing to fund Defense if national leaders did not clearly explain why they should make such great sacrifices of blood and treasure.

Polls and surveys say a lot about how that sentiment has continued since 1974, but basic math demonstrates more readily why policymakers must engage more fully with citizens on this topic:

Current plans are for the Pentagon to build 50 aircraft carriers before 2050 at a cost of $13 billion each, for a total of $650 billion (that doesn’t include the hundreds of aircraft or thousands of sailors to man each ship).

A school (an elaborate school in a large city) costs about $500 per square foot and on average runs $50 million to build.

So, in essence policymakers are telling citizens that they should be willing to give up building 13,000 schools in order to build 50 ships.

But… they’re not doing a good job of explaining why.

Even if policymakers try to justify such an expenditure by pointing out the large number of jobs created by building aircraft carriers, it doesn’t make the tradeoff acceptable to most citizens. That’s because any 10-year-old with a Husky Pencil and a Big Chief Tablet can calculate that manning 13,000 schools creates more jobs than building 50 ships. Moreover, the additional benefit those schools produce in educating the American workforce is priceless as a security multiplier.

So, should we call for a reduction in defense spending? Frankly, we do not know the answer because policymakers have been careful not to define what they mean when they talk about national security. It’s not defined in any law we can find, so it is impossible to know if we spend too much on it.

Instead, we are calling for a more holistic view of security (and national security) that is firmly grounded in what citizens view as their security needs. If those views are uninformed, then it is the job of policymakers to educate and lead…

In bringing this discussion… I must again refer to its incompleteness… I, for one, am fully convinced that the most formidable threats to this nation are in the nonmilitary field. Maxwell Taylor

What is the current citizen's view on security, and how was it formed?

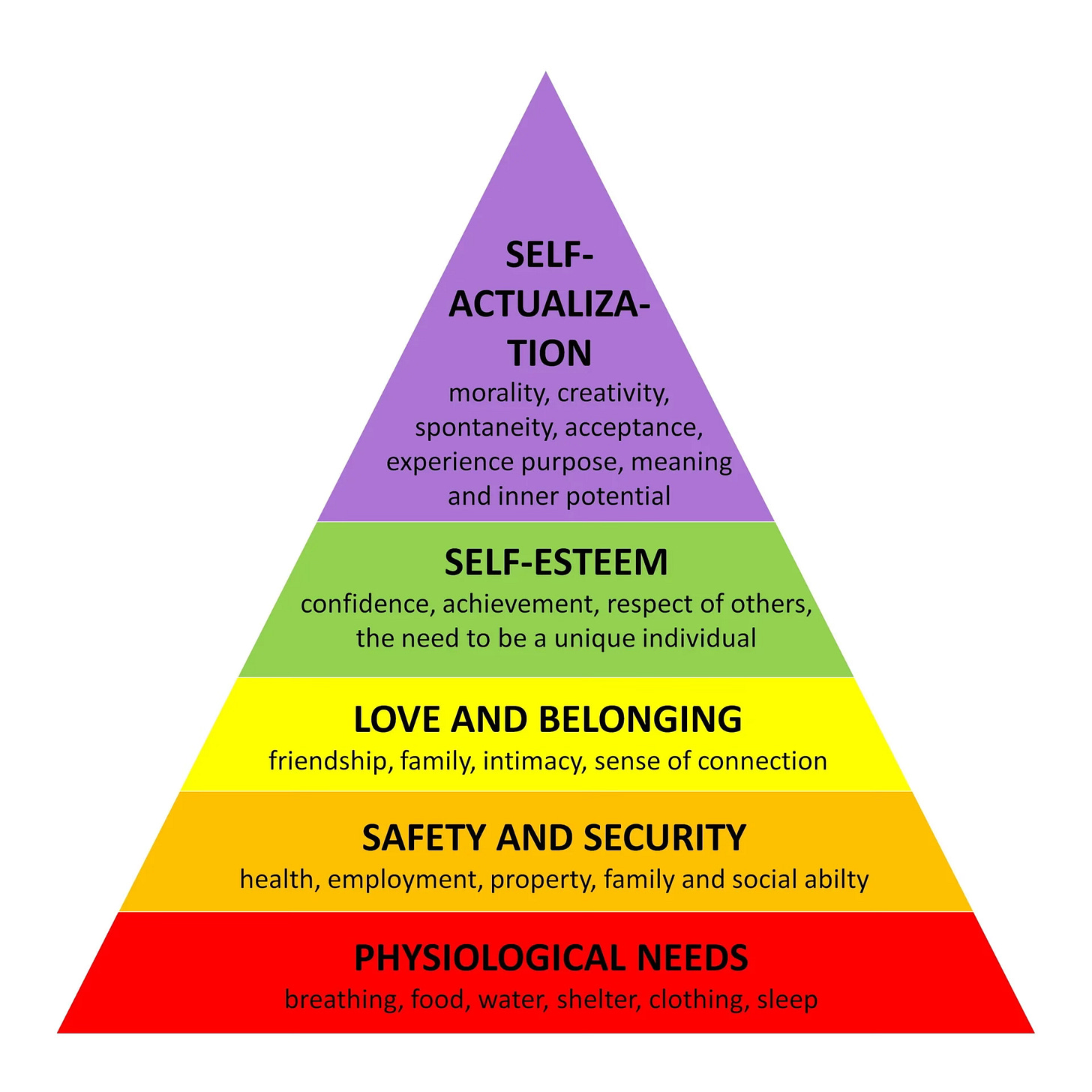

Most Americans (especially those my age) had their first formative discussion about security in a middle-school classroom, followed by a fill-in-the-blank or multiple-choice (if we were lucky) exam about Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs.

I’m unsure if I was in sixth or seventh grade when I was introduced to Maslow. I’m going to guess that I was in Ms. Peggy Maske’s 6th-grade class. But I have to admit that I didn’t pay nearly as much attention as I should have. And you probably didn’t either… So, for those of you (like me) who didn’t pay close attention and are two or more “Van Winkle naps” away from 6th grade, a refresher might be in order on Maslow.

Maslow’s Hierarchy is a construct for understanding human behavior developed in the 1940s by Abraham Maslow, an American psychology professor. The Hierarchy describes human “needs” (or deficits). It is made of successive levels and usually drawn in the form of a pyramid, with the needs of each level explained.

There was no School House Rock episode made for Maslow’s Hierarchy -I have petitioned Congress several times to require a School House Rock episode for every important topic- but the foundational arguments proposed by Maslow as laid out in that “pre-Pride,” rainbow pyramid stuck with us anyway; probably because most of what Maslow offered is common sense.

Human activity is driven by need. Humans need to eat; that existential need (or food deficit) significantly influences our actions. Likewise, the need to feel safe, loved, warm, rested, and in good health influences our actions and decisions. If you ask most Americans today what they mean by security, the answers that you get will pretty closely mirror the first two levels of Maslow’s Hierarchy.

Maslow’s Hierarchy has fallen out of vogue a bit over the years and has been criticized as sexist, classist, Western, and too rigid (poor Maslow). However, to be fair to Maslow, he was not the one who put his model into a pyramid; he recognized the framework as a general model; and he recognized that different individuals might prioritize their needs differently.

Later (1994), a bunch of smart people wrote a paper that sounded a lot like Maslow but did it in a way that was more politically correct. They called what we have just described “Human Security. "4 Human Security is comprised of Economic Security, Food Security, Health Security, Environmental Security, Personal Security, Community Security, and Political Security.

It turns out that those concepts are not only Malsowian but also pretty American. In fact, our founding documents probably served as the philosophical roots for those beliefs. Human Security sounds a lot like establishing justice, ensuring domestic tranquility, providing for the common defense, promoting the general welfare, and securing the blessings of liberty.

Those two sets of concepts advocate for the same things, and if we went through them one at a time, in plain language, we would see that the overwhelming majority of Americans agree with them as well. Where we find disagreement is usually in how to gain that security and prioritize its components.

General Taylor made those very points in “The Legitimate Claims of National Security.” He focused his essay on prioritizing security and gaining consensus for our national security aims. He also warned policymakers that if the taxpayer feels that we are prioritizing aircraft carriers over schools and fighter aircraft over infrastructure to the degree that it harms the citizenry, the people will stop funding defense at necessary levels.

In the end, I feel a bit sorry for General Taylor. It’s sad to read his essay. I can feel him coming to grips with the realization (after a lifetime of service) that what he thought was the most important thing… was not the most important thing to the American people. I imagine that realization was a hard pill for General Taylor to swallow.

General Taylor had spent his entire life focused on Defense and thought it to be the most important thing. But the American people saw (see) Defense not as an end unto itself. They see it as a means to promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty.

Frankly, policymakers are in the same place (or worse) today. This leaves us with a three-part dilemma.

Can policymakers move beyond tribal politics to address the wicked problems that we face today?

Can policymakers reframe their “National Security” views to be more holistic? How do they shift our National Strategy away from its singular fascination with Defense to a broader view that sees national Defense as a priority but focuses on larger issues?

Who in government should be responsible for connecting the dots?

General Taylor had some ideas about that and as you may have guessed… we have some ideas as well.

Our ideas are not revolutionary. We think they’re common-sense proposals that will not cost any more money, will not start a new government program, and are apolitical. Which means they probably won’t be acted on in a million years!!!

In the coming weeks, we will continue our series on Middle East Conflict and start some new conversations in a new section called “Decrypting Defense." Eventually, we will rejoin this conversation as we begin a new series that pulls our foundational discussions on strategy and security into a conversation about National Strategy and Government. We believe we have an interesting spin on National Strategy that you’ll enjoy discussing with us.

Finally, in closing, we ask for a moment of reflection.

If you consumed any infotainment (formerly known as news) on any media platform in the last 24 hours, the odds are that you didn’t hear anyone discussing ways to promote the general welfare and secure the blessings of liberty for the people of our nation. Those words (if they had come up) would have been dismissed as old-fashioned and cliche. Instead, you were probably fed a steady diet of controversy and bickering by left and right-wing policymakers who spent their time dismissing their opponents as irrational or deluded.

That’s pure laziness and much easier than figuring out policy solutions.

However, as our Founders laid out, promoting general welfare and securing the blessings of liberty are the primary missions of government. It’s not some dream or philosophical argument. It’s the damn job.

Let’s get to work!!

Weisner, Molly. “Trust in Government Hits Fresh Lows Ahead of US Presidential Election.” Federal Times, 10 June 2024, https://www.federaltimes.com/management/career/2024/06/10/trust-in-government-hits-fresh-lows-ahead-of-us-presidential-election/.

Taylor, Maxwell D. “The Legitimate Claims of National Security.” Foreign Affairs 52, no. 3 (1974): 577. https://doi.org/10.2307/20038070.

I would recommend: “Dereliction of Duty Reconsidered: The Book that Made the National Security Advisor” as a review of McMaster’s thoughts.

Nations, United. Human Development Report 1994. United Nations, 1 Jan. 1994, https://hdr.undp.org/content/human-development-report-1994.

Good article. Gerrymandering is the cause of our current political tribalism. Politicians no longer have to lead from the middle. I call it the Addams Family Effect. While inside the mansion, the characters are a little kooky and spooky, but normal amongst themselves. It is only when they leave the mansion and enter the outside world can a true level of spookiness and kookiness be realized (The Munsters, too). As well, I agree with your comments about the mission of defense. It is to protect what makes the USA great, which is not the defense, per se. Most bureaucracies suffer from goal displacement in which the true mission is pushed aside and replaced with self-sustainment. A need to stay alive and keep funding flowing. I saw this happen during the transition from USARSA to WHINSEC. We no longer were content just executing our mission to train and educate, foster friendships, and promote democracy. We had to promote ourselves as doing things we had no responsibility for, but got blamed for when things didn’t go as planned or there was blowback. The mendacity and puffery just blew my mind sometimes as we tried to be everything to everyone seeking political support and a budget line in the NDAA.